US Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts will not be present at the US Court of Appeals in DC when T-Mobile appeals an $80 million FCC fine; however, the opinion he wrote in the 6 to 3 vote released Friday regarding Chevron deference will be, and the court might be more critical of the methodology used by the FCC to arrive at the fine regarding T-Mobile’s mobile device location actions.

On February 27, unaware that the following day, the US Supreme Court would decide to limit the broad regulatory authority of federal agencies such as the FCC, T-Mobile USA, Inc. filed a petition for review in the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, contesting a substantial forfeiture order issued by the agency.

Missouri Sheriff Cory Hutcheson wanted to get tough on drug dealers but spent six months in prison after being convicted of illegally tracking mobile phone users without a warrant by GPS locations services provider Securus Technologies. He could have faced up to 20 months but skated on a sweetheart deal. However, the FCC got tough on the major carriers who allowed alleged unlawful GPS access with a $200 million fine. T-Mobile is appealing the decision and will likely be helped by Friday’s US Supreme Court decision.

The outcome of this case, likely influenced by the SCOTUS decision, could set a precedent for how federal agencies interpret and enforce ambiguous statutes. A ruling favoring T-Mobile could limit the FCC’s future regulatory actions and interpretations, particularly concerning new or evolving technologies and data privacy concerns.

The proposed $80 million fine against T-Mobile and additional fines for three other carriers stemmed from allegations of mishandling customer proprietary network information (CPNI), specifically mobile device location data.

The dispute centers on a 2018 revelation that leading US wireless carriers, including T-Mobile, had been sharing real-time location data with third-party aggregators without obtaining proper customer consent. This practice came to light following reports that a Missouri sheriff had used a location-finding service to track mobile phone users illegally. In response, the FCC initiated enforcement actions against AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon, resulting in nearly $200 million in fines.

On April 29, 2024, a divided FCC, in a 3-2 vote, with Republican Commissioners Brendan Carr and Nathan Simington dissenting, concluded that T-Mobile violated Section 222 of the Communications Act and related regulations. The Commission imposed an $80 million penalty on T-Mobile, asserting that the company failed to take reasonable measures to protect against unauthorized access to customer location data unrelated to voice calls.

The majority opinion of the order argued that mobile device location information falls under the category of CPNI, thereby mandating strict protection protocols. Carr contended that the FCC’s interpretation of CPNI was overreaching and lacked fair notice, while Simington criticized the penalty’s calculation methodology as arbitrary and exceeding statutory limits.

T-Mobile has labeled the FCC’s order as “unlawful, arbitrary, and capricious,” asserting several vital points:

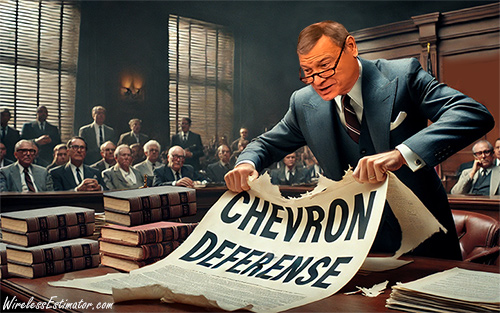

SHREDDING 40 YEARS OF STANDING – The US Supreme Court overruled Chevron deference in its decision on June 28, 2024. Chevron – a central doctrine of administrative law – had stood since 1984. In a 6-3 decision, the Court held that Chevron, which grants significant deference to agency interpretations of federal statutes, conflicts with the Administrative Procedure Act’s (APA) command that courts, not agencies, are to “decide all relevant questions of law” and “interpret statutory provisions.” Despite overturning Chevron, the Supreme Court emphasized that the ruling does not invalidate prior cases decided under the Chevron framework.

T-Mobile argues that the location information does not constitute CPNI under Section 222, as traditionally interpreted by the Commission. They claim the FCC overstepped its regulatory boundaries by retroactively applying new legal standards.

The company asserts that it was punished based on newly established requirements that were not previously communicated, thus violating principles of fair notice.

T-Mobile contends that the $80 million fine is disproportionate and calculated by arbitrarily subdividing a single incident into multiple violations. They maintain that this approach must be consistent with the Commission’s precedents.

The petition argues that the FCC’s unilateral imposition of the fine infringes on T-Mobile’s constitutional rights to a jury trial and due process, given the agency’s role as both prosecutor and judge in the enforcement proceeding.

T-Mobile insists that it had implemented numerous safeguards to protect customer data and acted swiftly to address any misuse. They claim the FCC’s expectation to terminate essential location-based services within 30 days of a data misuse report was unreasonable and detrimental to customers.

This case highlights ongoing tensions between regulatory authorities and telecommunications companies over data privacy and consumer protection. The outcome of T-Mobile’s petition could set significant precedents for how customer location data is regulated and protected.

The other three carriers have indicated plans to appeal the FCC’s decisions, suggesting a protracted legal battle ahead. Commissioner Carr has voiced that the case may be better suited for the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), emphasizing that the FCC’s broadened definition of CPNI and the retroactive application of fines lacked a solid legal foundation.

The recent Supreme Court decision affecting Chevron deference has significant implications for T-Mobile’s legal challenge against the FCC’s forfeiture order. Chevron deference, a doctrine established in Chevron USA, Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., allows courts to defer to a federal agency’s interpretation of ambiguous laws that the agency administers, provided the interpretation is reasonable.

Courts will no longer automatically defer to the FCC’s interpretation of the Communications Act, particularly Section 222 regarding CPNI. T-Mobile can argue that the FCC’s expansive interpretation of CPNI, which includes mobile device location information, is not entitled to judicial deference and should be scrutinized more rigorously.

The DC Circuit Court would now more closely examine whether the FCC’s interpretation of the statute is correct rather than merely reasonable. This higher level of scrutiny could benefit T-Mobile, which argues that the FCC overstepped its statutory authority.

T-Mobile contends that the FCC failed to provide fair notice of its novel interpretation of CPNI. Without Chevron deference, the court may be more inclined to agree that T-Mobile was unfairly penalized based on a sudden and unexpected change in regulatory interpretation, thus violating principles of fair notice.

The lack of Chevron deference could also impact how the court views the FCC’s method of calculating penalties. T-Mobile argues that the penalty imposed is arbitrary and capricious. Without deference to the FCC’s expertise, the court might be more critical of the methodology used to arrive at the $80 million fine.

T-Mobile’s constitutional arguments might receive more favorable consideration, including the claim that the FCC acted as investigator, prosecutor, and judge. The court may be more receptive to these arguments if it is less willing to defer to the FCC’s expertise and authority in interpreting its powers.

The challenge to the FCC’s forfeiture authority under the non-delegation doctrine could be bolstered. Without Chevron deference, the court might be more critical of whether Congress provided sufficient guidance in the statute regarding the FCC’s ability to impose such penalties.

The recent Supreme Court decision affecting Chevron deference will likely strengthen T-Mobile’s position by reducing the judicial deference typically afforded to the FCC’s interpretation of ambiguous statutory provisions. This could lead to a more stringent review of the FCC’s actions and potentially increase the likelihood of T-Mobile’s petition being granted.