As the FCC and President Donald Trump’s administration push to Make America Great Again by accelerating 5G deployment, questions raised under the “Make America Healthy Again” banner highlight a potential tension over RF safety—though, for now, those concerns appear unlikely to impede the administration’s pro-5G agenda materially.

As the FCC advances a deregulatory push to accelerate 5G and soon 6G infrastructure deployments, a potentially competing health-policy track is emerging within the Trump administration: Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is moving to launch a new federal study examining the health risks of cellphone radiation.

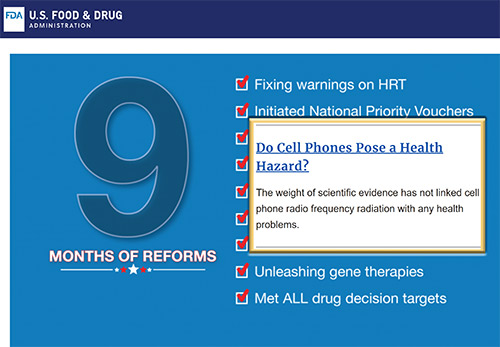

The FDA continues to maintain a consumer-facing page stating that scientific evidence does not show a danger to users from radio frequency exposure, noting that “the weight of scientific evidence has not linked cell phone radio frequency radiation with any health problems.” At the same time, the agency has removed other webpages that more explicitly stated cell phones pose no health risk—fueling confusion and media concern despite no change in the FDA’s core scientific position.

The development is surfacing just as the FCC wraps the comment cycle on a wireless infrastructure NPRM designed to streamline permitting and reduce state and local obstacles to network buildouts—an initiative the Commission has framed as “supercharging” deployment, densification, and upgrades.

The immediate market risk to carriers, tower owners, and contractors appears limited, however, because the FCC’s RF exposure framework remains intact and is deeply embedded in federal policy and device authorization.

The FCC continues to publish RF safety guidance and consumer-facing materials that explain that wireless devices must comply with exposure limits (including the 1.6 W/kg SAR limit for handsets) and outline the agency’s view of the state of the science and how compliance is measured. While Kennedy’s HHS is signaling a more aggressive posture—Reuters reported that HHS will initiate a study after the FDA removed older webpages that had said cellphones are not dangerous—those changes have not, by themselves, altered the FCC’s exposure rules or its current public guidance.

The FDA also continues to maintain a consumer page stating that scientific evidence does not show a danger to users from radiofrequency exposure, underscoring that federal messaging remains mixed rather than shifting uniformly.

The likely flashpoint is political and rhetorical more than regulatory—at least in the near term. Kennedy’s “Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA) framing could elevate public concern and spur hearings, research funding, and state-level school policies. Still, any attempt to translate that into tighter nationwide RF limits would be procedurally complex and would run directly into the FCC’s existing standards and the administration’s parallel pro-buildout agenda.

For the wireless infrastructure ecosystem, the practical takeaway is that the siting and deployment lane is still moving forward at the FCC, while the RF-safety lane is shifting toward additional study—potentially creating headlines and political pressure, but not an immediate rule change that would halt or materially slow ongoing 5G deployments.