Fifty years ago today, Martin (Marty) Cooper, an engineer for Motorola, stood nervously along 6th Avenue in New York City, about to trigger America’s love affair with mobility.

He reached into his pocket for a little telephone book and dialed a landline number on the cell phone he had invented.

It was part of his plan to razz his archcompetitor, Bell Labs’ Joel Engel, to let him know that he had lost the handheld mobile phone race. He started with: “Joel, this is Marty Cooper.”

It was part of his plan to razz his archcompetitor, Bell Labs’ Joel Engel, to let him know that he had lost the handheld mobile phone race. He started with: “Joel, this is Marty Cooper.”

“Joel, I’m calling you from a cell phone. But a real cell phone, a handheld, personal, portable cell phone,’” said Cooper. Years later, Engel said he may have received the call, but doesn’t remember Cooper’s utterance.

Popular and Wikipedia lore has it that if it wasn’t for Captain Kirk using his 1964 Communicator flip phone-like device, the cell phone might not have been invented.

However, in an interview with Wireless Estimator, Cooper said Dick Tracy’s 1946 two-way wrist radio was one of a number of seminal triggers for his inspiration, not Star Trek.

The cost per minute for a cell phone call in 1983 would be billed at approximately $.47 a minute. Adjusted for inflation, that cost would be $1.43.

The Marty Cooper you might not know

Martin Cooper was born on December 26, 1928, in Chicago, Ill., but he moved with his family back to Winnipeg, Canada, where his Russian immigrant parents, Arthur and Mary, tried out their entrepreneurial skills, but they moved back around 1935 and started a door-to-door sales business in Chicago.

Cooper told Wireless Estimator in an interview that he didn’t get the opportunity to go to the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933, where AT&T’s exhibit reigned supreme and thousands of lucky visitors got to make their very first long-distance call.

Cooper told Wireless Estimator in an interview that he didn’t get the opportunity to go to the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933, where AT&T’s exhibit reigned supreme and thousands of lucky visitors got to make their very first long-distance call.

Although that would surely have piqued his interest, everyday curiosities turned into a technical challenge for him.

At an early age, he recalls seeing some older kids setting fire to a piece of paper with a magnifying glass. He then took the base of a broken bottle and couldn’t understand why he couldn’t get it to focus and burn the sun.

Fortunately for the world, by 1973, his achievement scorecard read: Solar System – 0; Cellular System -1.

Cooper has two children, but they didn’t follow his career path; his son is an attorney and his daughter became an accountant; his four grandchildren are far removed from the engineering field as well, opting for professions from a piano prodigy to a sportscaster.

Encouraged by his parents, Cooper said he was an avid reader and lived in a household with his younger brother, Will, where he was always surrounded by books.

Cooper, who had already made up his mind that he was going to be an engineer, was enrolled in Crane Technical Preparatory High School in Chicago.

The males-only school was tough, not in an academic sense, but it provided an oftentimes threatening environment.

Of many shops, Cooper recalls that there was a forge shop where some students made brass knuckles. But he said there were several other shops that taught him a lot about science.

Around 2010, one student was fatally shot, and another was severely beaten with a golf club inside the Jackson Blvd. co-ed school, which has moved away from technical courses.

To attempt to quell the violence, Crane was invited to participate in the Txt2Tip program. Students are encouraged to send anonymous text messages to police – on the latest model of their Cooper-inspired cell phone.

It was a financial struggle for Cooper to attend the Illinois Institute of Technology. Still, once he was enrolled in 1946, they introduced a Navy ROTC program which he joined and they paid most of his tuition expenses, at that time $256 per semester.

He received his bachelor’s degree in 1950, a master’s degree in 1957, and was awarded an honorary doctorate in 2004. He currently serves on IIT’s Board of Trustees.

He is a member of the high-IQ society Mensa.

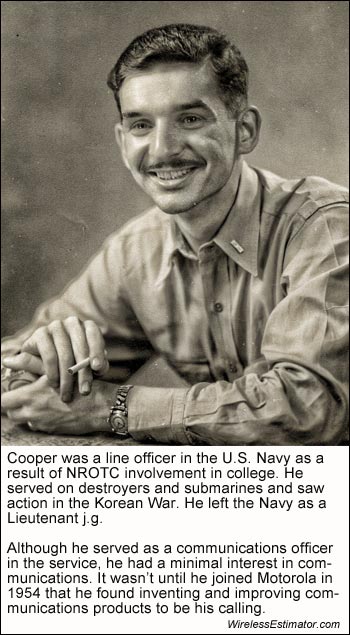

When Cooper graduated from IIT he went into the Navy and served on destroyers for a couple of years and then on submarines.

“I think the Navy was really an essential part of what I am today,” Cooper said.

Cooper served during the Korean War in the Yellow Sea on the U.S.S. Cony and recalls blowing up North Korean bridges for six months, and becoming frustrated because they would frequently rebuild them during the night and they would have to return the next day and do it again.

Although he served as a communications officer, he said he didn’t have much of an interest in communications.

“I have always been interested in anything technical, but my interest in communications didn’t start until I joined Motorola in 1954,” Cooper said.

Prior to that employment, he worked for Teletype Corporation, which provided a communications device that, like a mechanical typewriter, gave news organizations breaking news as well as providing quasi-secure messages to businesses.

Cooper held numerous positions at Motorola and directed the introduction of paging products, two-way radios, and nationwide car phones with 12 channels.

He also recruited many of Motorola’s top engineers.

Cooper left Motorola in 1983 to start, with two partners – one of whom is now his wife, Arlene Harris, also an inventor and a very successful entrepreneur – a new company that built software and billing systems for the new cellular industry that began that year.

The company was very successful and was sold in 1986.

He and Arlene then formed ArrayComm in 1992, a company providing multi-antenna signal (MAS) processing software and physical layer solutions for WiMAX and LTE wireless infrastructure and client device applications.

Their software was deployed in more than 300,000 base stations worldwide.

The firm has over 40 engineers, engineers that will hopefully confirm that “Cooper’s Law” can be extrapolated for the next 104 years, and spectrum challenges will be solved by technologists.

Cooper said that Motorola’s belief was that “Someday everybody in the world would have a cellular telephone. In fact, we had a joke that said, in the future, when you were born you would be assigned a telephone number, and if you didn’t answer the phone, you were dead.”