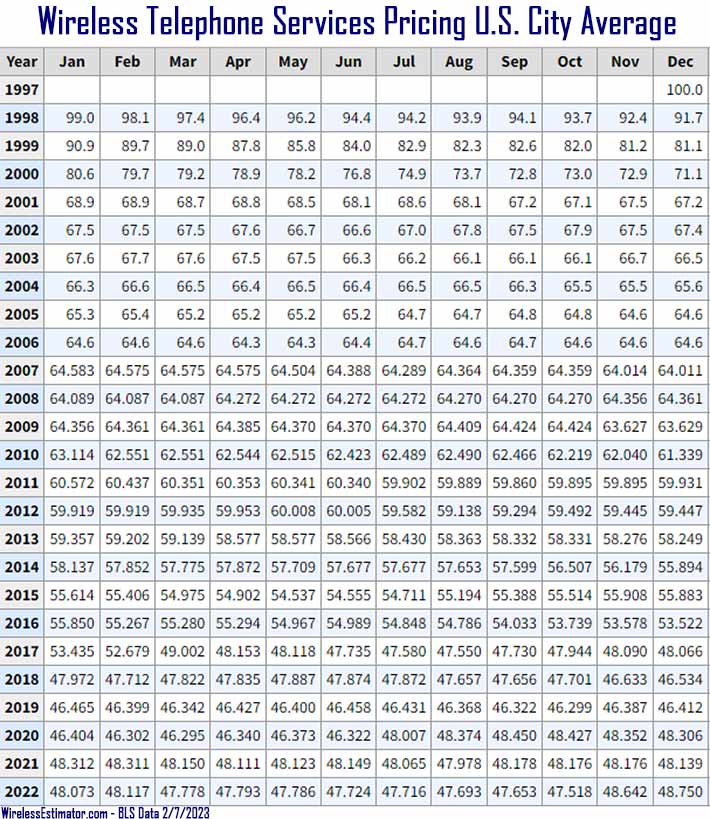

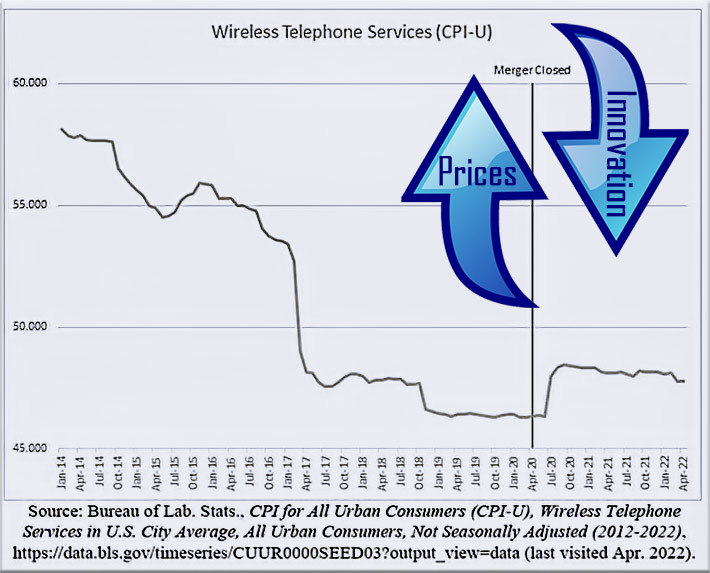

WIRELESS SERVICE PRICING, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in April 2020, when the T-Mobile/Sprint merger took place, was at $46.34. Two years later, it was at $47.79. In December, it was $48.75. A June 2022 lawsuit states that prices were dropping an average of 6.3% per year, but after the merger, they continued to rise. However, the carriers did not take advantage of the possibility of supporting up to a $5.00 per month increase being plotted, as stated in the plaintiffs’ response to a dismissal motion to overturn the merger lawsuit on Friday. (View wireless pricing since 1997 below)

In a motion by T-Mobile and SoftBank on December 5 to dismiss a lawsuit to overturn T-Mobile’s Sprint acquisition, the seven plaintiffs representing the class action said that the defendants claim that the “lawsuit seeks to turn the antitrust laws on their head.”

However, plaintiffs argue that the “case involves no gymnastics.” Instead, it advances claims that go to the heart of the Clayton and Sherman Acts. They state that the two enormous corporations combined to reduce competition and increase profits at the expense of consumers.

T-Mobile, in its motion, said the plaintiffs have failed to allege any anticompetitive effects. The plaintiffs said their claim came as a surprise since the concentration levels caused by the merger plainly meet the standard for anticompetitive harm.

They note that before the merger, retail wireless prices declined for years. After the merger, according to the best public data available, according to their motion, quality-adjusted prices jumped and stayed high, and all three carriers either raised their prices or did so surreptitiously through new taxes, fees, and surcharges.

“This was no accident – it was planned. The very executives who plotted the merger hypothesized that merging Sprint Corporation and T-Mobile US, Incorporated could support a $5 increase in ‘ARPU’ – Average Revenue Per User – across the entire market, including Verizon Communications, Inc. and AT&T Inc. customers,” the plaintiffs claim.

Plaintiffs: SoftBank chief Son, reportedly met with President-elect Trump to discuss merger environment

The complaint alleges that as early as 2010, Deutsche Telekom (DT) considered merging T-Mobile with Sprint to realize a four-to-three merger that, in DT’s words would “reduce price competition” and increase profits. And shortly after acquiring a majority interest of Sprint in 2014, SoftBank’s Chairman, Masayoshi Son, was on the news promoting the merger.

In 2016 he rushed to Trump Tower to meet with then-President-elect Trump, who reportedly told Son “that he would do a lot of deregulation during his term,” the motion states.

Post-merger concerns realized

The plaintiffs state that their worst fears have been realized. Prices have increased, innovation and consumer options have decreased, and “DISH appears to have no chance of becoming a viable fourth competitor.”

The defendants have stated that the plaintiffs “are not customers of the merging entities,” therefore the lawsuit should be thrown out. The plaintiffs argue that there are consistent court rulings that directly contradict their assertion.

Price increases had direct anticompetitive effects

The complaint makes detailed factual allegations about the increase in quality-adjusted prices following the merger. Prior to the merger announcement, prices for nationwide wireless plans had dropped by 6.3% per year for a decade.

According to the BLS, the official government agency which measures consumer prices, quality-adjusted consumer prices had been on a downward trend since at least January 2014.

Yet in the first three months after the merger closed (on April 18, 2020), quality-adjusted prices jumped.

“This happened despite T-Mobile’s promise to the district court that the merger would lead to lower prices and improved quality, not just for T-Mobile customers, but also AT&T’s and Verizon’s. Defendants contend that the BLS data—the best, most impartial public data—has not been quality-adjusted enough because it does not account for the shifting of plans from 4G to 5G. But defendants ignore the fact that the BLS, as the complaint explains, makes multiple quality adjustments, such as by accounting for differences like the amount of high-speed data, the number of lines offered, and other factors. Defendants want the BLS to account for 5G, but BLS believes it can publish accurate, usable data without making that adjustment and that the benefits of 5G above and beyond the adjustments it does make, if any, cannot be quantified,” the motion states.

They also emphasized that the defendants forgot to mention that very few customers had 5G at the time of the price jump.

Plaintiffs claim DISH is a weak fourth carrier

The plaintiffs state that although T-Mobile asserts that DISH has been deploying 5G as it promised, having already built out a 5G network in 120 cities, including Las Vegas and Spokane, “the question is not whether DISH has any network at all; the question is whether swapping DISH for Sprint increased competition or reduced it. This cannot be resolved on a motion to dismiss, especially given T-Mobile’s violation of the regulatory commitments that would supposedly support DISH. Even in Las Vegas, where DISH’s 5G service has the most towers, “there are still basic features missing which make it clear the service isn’t for the general public.”