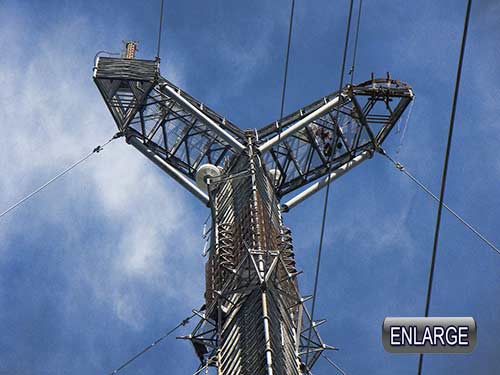

Inadequate rigging caused the 160-foot Klein gin pole to break lose from the Miami Gardens tower killing three tall tower erectors tied off to it on Sept. 27, 2017.

An OSHA Review Commission Judge has vacated a proposed $12,934 OSHA penalty against tall tower erection firm Tower King ll, Inc. of Cedar Hill, Texas that was issued following a tragic accident on Sept. 27, 2017 when a gin pole broke loose from a 958-foot WSVN TV tower in Miami Gardens, Florida after its bridle slings failed, killing three erectors, one of whom was the owner’s stepson.

It was found by OSHA’s and Tower King’s investigative teams that the reason the bridle slings failed was because of an engineering error. In calculating the load forces, the Stainless engineer hired by Tower King to provide an engineering review of their rigging plan made a “grievous error.” He assumed the connection points were seventy 70 feet apart rather than twelve 12 feet. This error caused the engineer to understate the load forces by a factor of at least 4.5.

Following an investigation, OSHA issued Tower King a single citation alleging a serious violation under the catch-all general duty clause, alleging that Tower King exposed employees to fall and struck by hazards posed by overloading of the rigging components resulting from its failure to have a complete rigging plan for the equipment attached to the tower.

Tower King owner Kevin Barber informed Wireless Estimator that it was very costly to mount a rigorous defense, but he said, “We knew we were right and we wanted the truth to prevail.”

It did, and in Judge Heather A. Joys’ decision that will be filed with the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission on July 17, 2019, essentially, OSHA was attempting to impose requirements on the industry that went far beyond the industry’s ANSI/ASSE A10.48 consensus standard, according to Tower King’s lead attorney, Tod T. Morrow of Morrow & Meyer, LLC of Canton, Ohio.

OSHA questioned abilities of a competent rigger

“OSHA took the position that an engineer must review all details of the rigging plan, including sling size, sling angles and fall protection attachment points. In essence, OSHA was saying that competent riggers were not competent to determine the means and methods of the rigging in the field,” said Morrow.

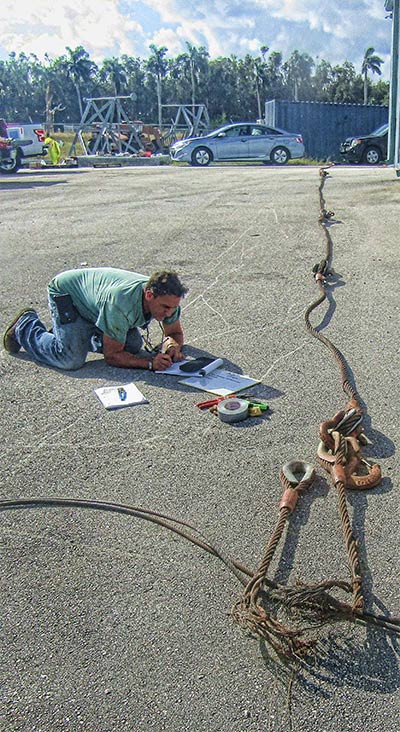

Slings and other rigging equipment were investigated by OSHA and Tower King ll’s team of experts following the gin pole failure. All of the rigging was sent to a laboratory for testing and all were determined to meet the manufacturer’s rated capacity and would have been sufficient for a safe installation based upon Stainless’ engineering that was later found to be flawed.

He believes OSHA’s decision to issue a citation, was an example of “Monday morning quarterbacking”’ of the worst sort.

“It appeared to me that OSHA issued a citation simply because an accident had occurred and then struggled to define what exactly the company had done wrong.”

Morrow noted, “OSHA continually changed its position throughout the case. Because OSHA lacked familiarity with the tower industry, it made a lot of mistakes in its investigation. When those mistakes were pointed out or revealed during the pre-hearing discovery process, OSHA would simply move on to some other alleged deficiency.”

Tower King had been hired by WSVN Channel 7, owned by Sunbeam Television Corporation, to replace a dummy pole and the pedestal it sat on with a new pedestal and an antenna. The erector, according to testimony, used a gin pole that it attached to the arbor of the tower to lower and lift the items. The gin pole, which was supposed to be 140 feet long, but which the workers made 160 feet, was attached to the arbor with rigging components consisting of slings and come-alongs.

OSHA’s original citation identified that Tower King exposed its employees to fall hazards which could be feasibly prevented by following and implementing ANSI/ASSE A10.48-2016, which required that a qualified engineer review the means and methods of the rigging attachments of the gin pole to the tower.

However, OSHA subsequently amended the citation to delete any reference to ANSI A10.48, stating that Tower King’s rigging plan was incomplete because it failed to include the means and methods of the rigging attachments for the gin pole to the structure which could be reviewed by a qualified engineer.

Requiring contractors to have rigging plans reviewed by an engineer is challenged

In his post-hearing brief, Morrow said that OSHA is requiring tower contractors to prepare detailed written rigging plans that must be reviewed by an engineer with respect to the means and methods of the tower rigging process.

“This practice is contrary to industry custom as well as the various national consensus tower safety standards, which involve a qualified engineer reviewing the rigging plan to calculate the load forces imposed on the tower, but not the means and methods of the rigging process. Typically, in the tower industry, the determination of the specific means and methods of the rigging is left to the expertise and discretion of experienced and competent riggers in the field,” said Morrow.

“This practice is contrary to industry custom as well as the various national consensus tower safety standards, which involve a qualified engineer reviewing the rigging plan to calculate the load forces imposed on the tower, but not the means and methods of the rigging process. Typically, in the tower industry, the determination of the specific means and methods of the rigging is left to the expertise and discretion of experienced and competent riggers in the field,” said Morrow.

Although the lead OSHA investigator in the case, Michael Marquez, testified that Tower King’s safety program was inadequate, he could not identify any specific areas where it was inadequate, except to claim that he interviewed two employees who demonstrated inadequate knowledge of ANSI A10.48.

He could not give any specifics and conceded that one of the witnesses demonstrated familiarity with that standard, according to Morrow.

The pot calling the kettle black?

OSHA’s interpretation of A10.48, according to Morrow, is based upon an erroneous reading of that standard by their engineering expert, Dr. Bryan Ewing, who upon cross-examination admitted to having no experience with the tower industry prior to the case, and his expertise was limited to masonry engineering.

However, Ewing is listed on OSHA’s staffing directory as a structural engineer and was deemed qualified to be the lead investigator in OSHA’s extensive report of an April 19, 2018 tower collapse in Fordland, Missouri that killed the owner of a tall tower erection company.

Morrow said that Ewing testified that he never even read the A10.48 standard until he was asked to provide guidance to OSHA.

Tower King ll owner Kevin Barber assisted OSHA in identifying rigging that was used on the tower such as this basket sling

“The basis for OSHA’s erroneous interpretation of A10.48 lies in their reading of Section 4.8, where it states in part: ‘A qualified engineer shall perform the analysis of structures and/or components for Class IV construction’,” Morrow said.

He notes that OSHA believes that this section refers to an engineer analysis of the contractor’s rigging system components.

Expert witness Jocko Vermillion, Vice President of Operations, CITCA, LLC, a former OSHA Compliance Office recognized as the agency’s national tower safety expert, and who helped write A10.48, explained to Judge Joys during the hearing in Fort Lauderdale, Florida that this sentence refers to the engineer’s analysis of the tower structure and components under TIA-322.

He said it does not refer to an engineer analysis of the contractor’s “rigging system components” or the means and methods of the rigging.

Vermillion explained, the ANSI Committee defined “rigging system components” to differentiate between tower components and rigging components, identifying that tower components are items such as pins and bolts and guy wires that hold the tower structure together.

Gin pole length addition, sling angles challenged, but rebutted

OSHA argued that Tower King created a hazard by deviating from the original rigging plan by adding 20 feet to the gin pole and repositioning the tag line.

However, Tower King’s attorneys provided evidence showed that such deviations are normal in the tower construction industry, had no significant effect on the safety of the project, and actually improved the safety of the WSVN Project.

They said there was no dispute that the use of a longer gin pole did not cause the bridle connection to fail.

They noted that the added weight was insignificant — less than 5 percent deviation — and it actually improved safety by adding ballast to the gin pole below the fulcrum or lever arm.

Judge Joys in her decision said, “The record is thin regarding who made the decision, how it was made, and what, if any, steps were taken to ensure the use of the larger gin pole did not overload the structure or the rigging components.”

She said it was not the contents of the rigging plan submitted to Stainless that posed the hazard, but the deviation from that plan in the field after the engineer had certified the plan.

“The citation does not address deviations from the plan, but the contents of the plan. The Secretary cannot rely on the deviation from the plan to meet this element of his burden of proof,” Judge Joys said.

OSHA noted that the bridle connection was made with a sling angle of less than 30 degrees. In rating the capacity of rigging components, the manufacturer assumes a sling angle of no less than 30 degrees with a built-in safety factor of 5 to 1.

However, OSHA’s expert, Dr. Ewing, initially calculated the sling angle to have been 27 degrees, because he failed to account for the gin pole track. He then changed his calculation to 28.5 degrees.

Expert witness James Ruedlinger, Senior Vice-President of Engineering with Electronics Research, testified that a sling angle of 28.5 degrees rather than 30 degrees had a negligible effect on the load calculation, well below 5 percent. The difference of 1.5 degrees would have no material effect on the capacity of the rigging components, Ruedlinger said.

The Stainless candelabra tower, jointly owned by WPLG Channel 10 and WSVN Channel 7, was constructed by Tower King ll in 2009, and is 1,042’ to the top of the antennas. It has a 12’ wide face, 2-man elevator, 50’ separation between antennas (center to center between arbors) and the heaviest section is 26,500 lbs. Each section is 30’ in length and the total structure weighs 1,013,450 lbs. Leg diameters range from 6.63” to 7.5” and there is a total of 5 levels of guy wires with the biggest one, at a tension of 106,000 lbs., at 2-5/8”.

At the hearing Ruedlinger also testified that neither TIA-322 nor ANSI A10.48 require an engineer to review the means and methods of a contractor’s rigging plan. ANSI A10.48 only requires coordination of an engineer to determine the load forces. The contractor then uses these load forces to properly size the rigging attachments to safely perform the work, he said.

Morrow believes the most disingenuous of OSHA’s arguments is its contention that Tower King’s allegedly incomplete rigging plan caused the rigging attachments of the gin pole to be overloaded, thereby causing the bridle attachment to fail.

Belief that attachment details could have prevented accident seen as ‘ridiculous’

Investigator Marquez said, “The accident could have been prevented if details of the attachment components of the gin pole to the tower structure were evaluated by a qualified engineer.”

“This contention is ridiculous in light of the undisputed evidence and explicit recognition by the witnesses for both Tower King and the Secretary that the load calculations were erroneous in that Stainless understated the actual load forces by a factor of at least 4.5 times; the Tower King crew selected the appropriate rigging components to handle the loads calculated by Stainless; and the bridle connection failed only because Stainless had severely understated the actual forces involved in the operation,” Morrow said in his brief.

In her decision, Judge Joys emphasized that Ruedlinger, who was involved in the development of both standards, explained ANSI/ASSE A10.48 specifies the duties and responsibilities for contractors while ANSI/TIA-322 specifies those for engineers. The standards are intended to “work hand in hand,” she noted.

The two standards were written with the intent of creating an interactive process between the certifying engineer and the contractor performing the construction work and that both standards place responsibility for developing a rigging plan on the contractor.

‘Nonsensical’ standard interpretation rebuked by Judge Joys

‘Nonsensical’ standard interpretation rebuked by Judge Joys

In his post- brief, U.S. Department of Labor Senior Trial Attorney Dane L. Steffenson argued that in ANSI A10.48, Tower King “…erroneously concludes that because section 4.85 says components rather than ‘rigging components’ that it is referring to structural, and not rigging components. It would be nonsensical for this Standard, which is meant to address means and methods and to protect personnel, to exclude components or parts of the load path from the engineer’s analysis.”

Steffenson said OSHA did not give Tower King a reduction in the fine since their safety program “did not provide the employees the information required to ensure against the hazard cited. Tower King did not ensure that its employees calculated forces on all components or trained on that issue.”

Judge Joys’ decision disagreed.

“The Secretary has failed to meet his burden to establish Tower King failed to render its workplace free of a hazard recognized by Tower King or the telecommunications tower industry. He has failed to meet his burden to establish Tower King violated the general duty clause. The citation is accordingly vacated,” Judge Joys wrote.

“The tower industry is doing their work right and the government, isn’t,” Vermillion said, emphasizing that the win was a team effort.

Barber, a competent rigger who has an excellent industry reputation, said that WSVN requested that he continue the installation following the accident.

He said he used an identical 160-foot Klein gin pole and had another engineer provide load forces.

Barber has rebuilt his business back to two six-man crews and he says he is busy with repack work.

The gin pole track remained on the arbor after the pole’s rigging failed

distance between the bridle and basket attachments (lever arm) was approximately 70 ft. However, the gin pole was, in fact, attached to the arbor and not to the tower resulting in a much shorter lever arm of approximately 12 ft. Therefore the assumption of a lever arm of 70 ft. resulted in significantly lower forces and proved to be a grievous error on the part of Stainless. Under the lifting condition of 11,000 pounds, Stainless computed the tension at the bridle location was approximately 3,300 pounds. However, our independent computations indicated that the forces at the bridle location would be approximately 15,000 pounds.”

distance between the bridle and basket attachments (lever arm) was approximately 70 ft. However, the gin pole was, in fact, attached to the arbor and not to the tower resulting in a much shorter lever arm of approximately 12 ft. Therefore the assumption of a lever arm of 70 ft. resulted in significantly lower forces and proved to be a grievous error on the part of Stainless. Under the lifting condition of 11,000 pounds, Stainless computed the tension at the bridle location was approximately 3,300 pounds. However, our independent computations indicated that the forces at the bridle location would be approximately 15,000 pounds.”