Byrd Telcom argued that OSHA should not have cited them after two of their employees died. Byrd said their gin pole was properly marked as detailed in ANSI/TIA-1019-A. An appellate court disagreed. The company reportedly forged documents following the death of their men to identify that they were not full-time employees, but independent contractors.

Based upon substantial evidence to support their findings, a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has kayoed a wireless contractor’s final attempt to vacate the company’s serious violations of OSHA’s General Duty Clause and $7,000 in fines they received following an accident that killed two of their employees on May 28, 2013.

Following the accident, investigators found part of the failed carabiner still lodged in a leg flange plate hole. However, it was found that the narrow part of the carabiner did not lend itself to accommodate the hook in the position in which the failed carabiner was found.

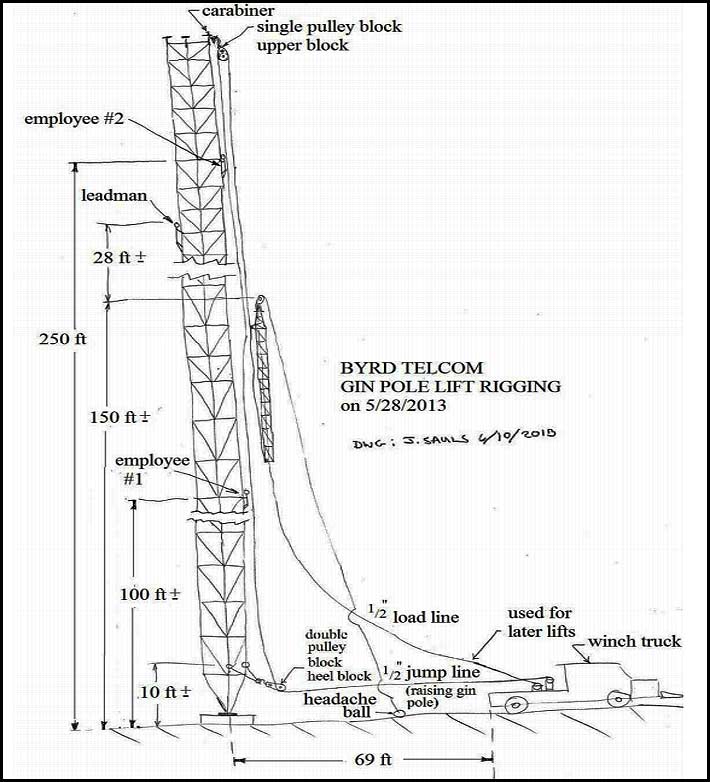

Both men, employees of Byrd Telcom of Lubbock County Tex., were performing work for Verizon Wireless on a 300-foot guyed tower in Georgetown, Miss. when a gin pole broke loose as it was being hoisted up the tower’s face because it was not properly rigged.

The incorrect use and failure of a carabiner appeared to have caused the 40-foot gin pole to fall from the structure with such force that it ripped the D rings out of the fall protection harnesses of both technicians and decapitated one of the workers. One of the tower techs had only been in the business for six months.

Crew members panic and leave site

According to the OSHA investigation, an unthinkable crew reaction occurred as soon as the gin pole fell and the two men were laying inside the fenced compound, approximately 14 feet next to each other: “Panic ensued at the site, and everyone jumped into their vehicles and left the site…”.

The experienced winch operator, who had only been on the job for one day, called 911 and remained at the site. The other four crew members were later contacted and returned to the accident scene.

The operator said he wasn’t aware that a carabiner, not designed for construction, had been used to rig the jump line block.

At the time of the accident, Byrd, a subcontractor to Andrew, had been in business approximately six months, according to OSHA’s investigation.

First defense: Crew members were independent contractors

During a hearing in 2015 before Administrate Law Judge (ALJ) John B. Gatto, the company’s owners, Lloyd “Sonny” Byrd and Ravan Rochelle Ray Byrd, claimed that the deceased workers were independent contractors and not employees.

However, Gatto disagreed, stating that Ravan and Sonny presented fraudulent documents following the fatalities to insulate themselves from liability, and concluded that there was a preponderance of evidence to show that the workers were employees, especially since their independent contractor W9 forms were forged.

He also upheld the citation issued under the “General Duty” clause because the workers “were exposed to struck-by hazards while raising a gin pole and were not protected by a properly secured top (hook) block used in raising a gin pole,” and “the gin pole was not permanently marked with an identification number that references a specific load chart and gin pole weight, thereby exposing employees on and near the tower to struck-by hazards while raising the gin pole.”

Circuit court affirms ALJ’s decision

Byrd appealed the ALJ’s 2015 decision and the three-judge appellate panel heard oral arguments on Sept. 27, 2016, and denied the company’s petition for review of the citation on Oct. 28, 2016.

The justices said that there was no dispute that rigging a gin pole by using a carabiner, which is not designed to be used for construction, is a hazardous activity, especially when it involves work on a tall tower. They said it carries with it a “substantial probability that death or serious physical harm may result”.

Second defense: Employee didn’t follow company guidelines

Although Byrd’s employee, by using a carabiner, deviated from the standard practice of rigging the jump line block by using chokers on the two tower legs and using a shackle at the center of the face of the tower to hang the block, his conduct was “unforeseeable, implausible, and therefore unpreventable,” and not in conformance with company policy, Byrd said in its defense. The justices found Byrd’s contention unconvincing.

Failed carabiner at the hook

They held that substantial evidence supported that Byrd had an inadequate safety program and had no work rules designed to address the proper rigging of a gin pole, and did not train employees to prepare them to rig a gin pole.

During the hearing, Byrd argued that OSHA was incorrectly interpreting the ANSI/TIA-1019-A standard that each gin pole section should be marked, and a single marking would be sufficient.

The standard reads:

- Each gin pole assembly and associated rooster head shall be permanently marked or otherwise clearly referenced for identification to its load chart.

- The gin pole installation documents shall identify sections requiring a specific installation sequence and the sections shall be appropriately marked.

- If a track is used to lift, or jump a gin pole, it shall be identified and acceptable rigging arrangements shall be included in the installation documents.

The OSHA inspector had found that the gin pole sections at the worksite on the day of the accident were not marked.

Byrd’s gin pole consists of four sections, two white, one red and one blue. The exhibits offered by Byrd into evidence indicated that a white pole section was stamped with an identification number.

The appellate judges noted, however, that the ALJ discovered that the white section had not been on the jobsite and the red and blue sections were not stamped.

Justices find pole sections weren’t marked

In their statement confirming the Commission’s order, the justices wrote, “We hold that substantial evidence exists to support the finding that the gin pole sections on site when the accident occurred were not marked, and thus that Byrd Telcom committed a serious violation of the General Duty Clause in Instance (c).”

Not only did the ALJ find that the on-site gin pole sections were not marked, but he also found that the corresponding load chart was not present on the site, preventing employees to accurately identify the load chart requirement and verify the load prior to the lift.”

“Because we find that the gin pole sections were not properly marked, we need not inquire into whether the industry standard demands that all sections of a gin pole be marked, or whether a single marking will suffice. Rather, we find that the unmarked gin pole sections and absence of a correct load chart generated a substantial probability that death or physical harm would result and thus constituted a serious violation.”

The OSH Act defines a “serious violation” as follows: “For purposes of this section, a serious violation shall be deemed to exist in a place of employment if there is a substantial probability that death or serious physical harm could result from a condition which exists, or from one or more practices, means, methods, operations, or processes which have been adopted or are in use, in such place of employment unless the employer did not, and could not with the exercise of reasonable diligence, know of the presence of the violation.”

OSHA met those elements under the General Duty Clause, the justices said.

In addition to challenging the serious violations, Byrd attacked with its brief and during oral argument the ALJ’s finding that his foreman was a credible witness. The Justices said they found no support for Byrd’s argument.

In an October 2013 OSHA investigation of the gin pole rigging that failed on the SBA Communications tower, following the accident investigators found part of the failed carabiner still lodged in a leg flange plate hole. However, it was found that the narrow part of the carabiner did not lend itself to accommodate the hook in the position in which the failed carabiner was found.

Insurance carriers also allege fraud by Byrd

Following the discovery of forged documents in the 2015 ALJ hearing, fraud charges were not filed.

Fraudulent activity was also alleged following the two techs’ deaths when in December of 2013 Byrd filed a lawsuit against two insurance carriers who denied workers compensation and indemnity coverage to Byrd, stating that the company misrepresented the scope of work it was performing on the Verizon 4G upgrade and other projects, identifying their scope of services as “normal electrical work within buildings”.

Byrd also said it had only one full time employee, according to the carriers.

Byrd’s breach of contract complaint stated that following the fatalities the insurance carriers canceled their policies.

Under the Texas Workers’ Compensation Act, where the lawsuit was filed, the term “employee” expressly excludes “independent contractor or the employee of an independent contractor.”

On December 2, 2014, a U.S. District Court Judge dismissed Byrd’s complaint.

The Court also said that Byrd’s request for the insurers to indemnify the company would not be considered since there has been no judgment against the plaintiff, although there currently are lawsuits and the insurers are defending Byrd, but they reserved the right to dispute their duty to pay a judgment.

OSHA investigators theorize that the crew’s lead hand was trying to pull the gin pole towards the center of the 3-foot face of the tower, thus applying additional side load to the hook and the carabiner, contributing to the failure of the carabiner. Drawing: John Sauls, P.E., Safety Engineer, Jackson Area Office, MS