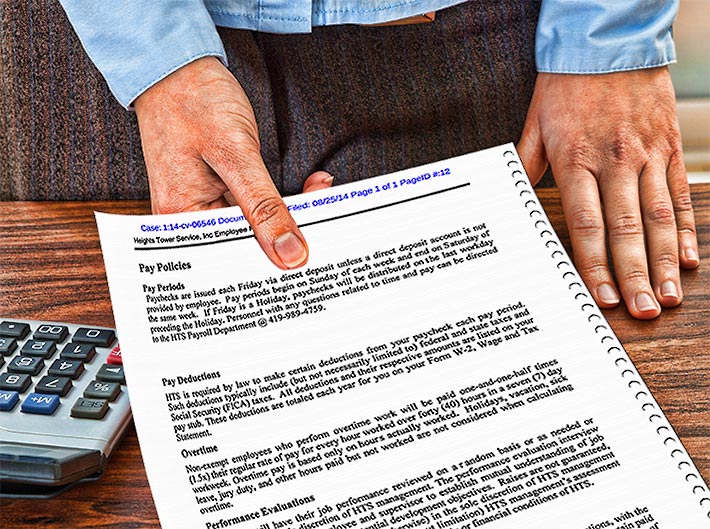

Heights Tower Service, according to a court document, has a policy in their handbook that states non-exempt employees who perform overtime work will be paid one-and-one-half times their regular rate of pay. A class action lawsuit claims that the company should have included travel time for every hour worked past 40 instead of paying employees a flat $10 per hour.

An Illinois class action lawsuit filed in August of 2014 by current and former tower techs of Heights Tower Service, Inc. (HTS) could be headed for a jury trial after a U.S. District Court Judge on Nov. 29 ruled against both sides’ bids for summary judgment regarding the complaint that accuses HTS of failing to properly compensate its employees for time spent driving to and returning from job sites.

U.S. Magistrate Judge Jeffrey T. Gilbert said he found insufficient evidence from the plaintiffs and the defendants to support their arguments for summary judgment. He also ruled against HTS’s motion to decertify the lawsuit as a class action.

HTS’s president and owner of the Mt. Vernon, Ohio wireless service company founded in 2010, Mark Motter, is also a defendant in the complaint.

Heights Tower Service said that when employees worked in their warehouse they were payed their hourly wages that counted towards overtime

The lawsuit is expected to be closely followed by many of the more than 1,200 industry service and installation contractors who may have the same policy that HTS follows.

Jason Pietrzycki, a former HTS employee, filed the lawsuit stating that he was paid $23 per hour, and would receive time and one-half pay, $34.50 an hour for every hour he worked over 40 hours, as required by law.

But Peitrzycki claims that HTS would exclude the time spent during “drive time” in computing overtime hours, and while in a vehicle as a passenger he was only paid $10 an hour, according to the lawsuit.

One paystub that was cited in the action detailed that during one week Peitrzycki had 39.50 hours of regular time and 6.5 hours of drive time, but he was not paid any overtime for the week, which put his gross wages at $973.50 rather than $1,115.50.

Pietrzycki claims that there are estimated to be over 100 current and former HTS employees within the class.

HTS’s handbook states that overtime will be paid for every hour over 40 hours in a 7-day week for “only hours that are actually worked”.

Prior to oral arguments that were heard on July 31, 2017, Gilbert said that the parties should be prepared to answer questions such as how do defendants respond to plaintiffs’ argument that riding as a passenger is a principal activity because defendants sometimes charge their customers for that time?

During the hearing it was stated that employees are allowed to arrange their own transportation if they want to do so. Typically, this involves driving a personal vehicle or riding in another crew member’s personal vehicle. Alternatively, HTS provides a free transportation option, allowing a crew’s members to travel in an HTS-owned truck to and from their tower site, but most of the time employees used the HTS truck for transportation.

HTS said in 2012, the company decided to implement the $10 per hour drive time policy “so that it could remain compensation-competitive and attract employees.”

However, time spent driving an HTS vehicle was recorded as normal work hours.

Gilbert said that the plaintiffs contend that the defendants bear the burden of providing drive time is not hours worked, but he said they bear the burden to provide that they performed overtime work for which they were not properly compensated.

Department of Labor regulations state that “The principles which apply in determining whether or not time spent in travel is working time depend upon the kind of travel involved.”

Gilbert noted in his ruling that an employee who travels from home before his regular workday and returns to his home at the end of the workday is engaged in ordinary home to work travel which is a normal incident of employment, and not worktime.

He said this rule applies even where employees travel together to a work site, either in an employee’s vehicle or a company-owned vehicle.

Gilbert said the rule also applies even when an employee works “at different job sites” instead of at a fixed location, and therefore the plaintiffs must show that drive time involves more than ordinary home-to-work travel.

The plaintiffs provided three cases to support their argument that a custom, practice or contract of compensating for travel time can make that time count as hours worked, but Gilbert said none of the cases supported their proposition.

The plaintiffs argued that their drive time was not a run of the mill home-to-work case.

They pointed out that when traveling in HTS trucks, they went to designated meeting locations and did not commute directly from or to home.

Gilbert said he wasn’t convinced by their arguments that they presented and said, “HTS did not require employees to go to a designated meeting site at the start or end of the day. Instead, they were free to go directly from their homes to their assigned towers at the start of the day and directly to their homes from their assigned towers at the end of the day. HTS also did not require employees to travel in an HTS truck.”

The plaintiffs argued that at least some drive town counted as hours worked under the “continuous workday rule,” which also is known as the “whistle-to-whistle rule,” because employees sometimes performed work at a warehouse either before traveling to the first tower of the day or after traveling back from the last tower of the day.

However, Gilbert said that the plaintiffs addressed the activities in the warehouse in a “haphazard and incomplete manner again, depriving the Court of an adequate record on which to decide the summary judgment motions.”

The plaintiffs stated that pre-trip activities benefited HTS because they helped crews get to towers faster and that the activities were integral to the employees’ work because the tasks had to be completed before going to a tower.

They contend that the pre-trip activities took 30 or more minutes and they were at times asked to do pre-trip activities and that, if they refused, they could be written up.

The plaintiffs also asserted that they performed work at customers’ warehouses, including loading materials, on their way to towers.

The defendants claimed that tower technicians were not required or directed to perform the pre-trip activities they described and they rarely performed work-related activities at HTS’s warehouse and “normally only loaded their personal belongings into an HTS truck.”

They also stated that when there was work to be performed at the warehouse they were paid their regular wages.

In his ruling, Gilbert said, “To the extent employees spent periods of time performing activities such as loading HTS trucks, the Court does not see why that would not be sufficient to mark the start of their workdays. Although there is a genuine issue of material fact as to whether employees are required to perform these activities, they are done for HTS’s benefit and are integral and indispensable to the principal activities performed at towers. But this is not enough on its own for the Court to find drive time counts as hours worked.”

The plaintiffs argued that at least some of their drive time should count as hours worked because, at times, employees performed other compensable work while traveling as passengers.

However, during oral argument the plaintiffs conceded that employees usually slept or otherwise used their time as they pleased and did not perform other activities that constituted work.

Nonetheless, on occasion the plaintiffs said some employees performed activities related to their work for HTS such as reviewing site plans, discussing job requirements and filling out paperwork, and having telephone calls with management.

Gilbert said that it sounded plausible “as a matter of common sense,” but he said that neither party had clearly shown how often employees performed any such activities.