|

Licensing climbers might help to stem the continued increase in industry fatalities

by Winton W. Wilcox Jr.

November 1, 2007 - Last February, Gritz Towers' management and employees struggled with a severe personal and emotional crisis when an employee died after falling from a 330-foot self supporting tower in Louisiana. supporting tower in Louisiana.

Less than six months later, they were devastated when another employee from Texas fell approximately 300 feet to his death, also in Louisiana.

After conducting thorough investigations following each accident, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration decided not to cite Gritz Towers for any workplace safety violations; after all, the company had provided its employees with adequate training and safety equipment, and had done everything right. But, despite these findings, the resolute burden of Gritz's management burns daily as they question whether this accident was preventable.

Perhaps now is the time for an industry-wide focus on tower climber safety and a collective effort by all companies involved in the construction infrastructure working to add an additional component to certification of tower climbers - licensing.

Could licensing have made a difference?

Gritz Towers of Goliad, Texas, is not a two men and a truck, rope and bucket shop. Established in 1979, this company is truly an industry leader that has always taken workplace safety seriously.

The Gruetzmachers are one of the tower industry's pioneer families and their name and personal ethics are intimate in their work. Recognizing that industry-wide licensing of tower climbers could possibly help prevent fatalities in the industry, the Gruetzmachers want to pave the way for regulation of tower climbers.

Since February, on an almost daily basis, Destry Gruetzmacher, the company's director of construction and redevelopment services, questions how tower climbing accidents can be prevented. Destry and the rest of the company's management team want answers. The status quo is simply not enough.

Today, even most small tower companies have a formal written safety plan. Climbers are increasingly provided with "certified" tower safety training and good quality safety equipment. The National Association of Tower Erectors prints industry-specific safety posters and communicates regularly with OSHA on issues related to the tower industry.

Employers are pressured by the government, their clients and the industry to meet their training, equipment and management responsibilities for safety. The industry writes thousands of safety meeting reports and job safety analysis and daily safety meeting documents; even the ANSI standard, TIA-EIA 222G, now directly addresses safety issues.

Revocation of certification questioned

Destry's challenge began by questioning whether a climber's "certification" could be revoked for not observing required safety guidelines while on a jobsite. Unfortunately, certification is verification of an accomplishment, not conduct. Simply put, you cannot revoke a college degree in accounting because the student is guilty of embezzlement.

Destry, not to be denied, then questioned, "What more can I as the employer do? When I hire a worker, how can I evaluate the climber's safety record? When I fire a climber for unsafe practices, he simply goes to work for another company the next day. How can the employer get the employee to buy into safety?"

While you cannot revoke certification, you can revoke a license. Furthermore, you can suspend a license and you can maintain records of infractions. When an employer hires a new worker, not only can he track the worker's driving record but the employer’s insurance provider will demand it. Couldn’t a similar notion work for tower climbers as well?

Destry may have his answer. Tower climbers need a license! Nearly every endeavor that includes danger, and is performed by individuals, requires a license. Doctors, nurses, drivers, beauticians, tree trimmers and real estate agents are required to be licensed. Why not tower climbers? How long would an unsafe long haul driver be trucking if he continually disobeyed speed limits, driving hours and safety policies?

The need to explore a reqirement for licensing is becoming apparent to many people who are directly concerned with safety in the tower industry.

A recent news article republished by PCIA, The Wireless Infrastructure Association, briefly discussed licensing, stating that, "Although most states regulate professions as prosaic as barbers, states require no license to climb a cell-phone tower. 'That breeds risk,' said Rob Medlock, an official in Cleveland with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration who took on climber safety as a personal project."

Licensing administration provides complicated issues

The answer seems so clear when talking to Destry, but implementation is complicated. Who has the authority to license? Generally, this is a government function, but what government agency has demonstrated any understanding of the issues involved with construction, maintenance and inspection of towers?

How do you focus the pressure to make it happen? What has the industry done to establish standards for skilled workers? What authority exists in the industry?

The Gruetzmachers' willingness to stand up and expose their concerns has led to several conversations regarding licensing questions: Who would administer such a license? What requirements would be listed and how would applicants acquire the prerequisites? What is the clear definition of a Tower Climber?

John Paul Jones, founder of Tower Safety and Service Co. of Austin, Texas, agrees with the idea of licensing, but also questions who would administrate it and how would that be accomplished?

John thinks the driving force should be the owners and clients of the communication companies, but wonders how to get them to focus on the need.

John Hettish of Middle Tennessee Two-way agrees in principle, but has concerns over how to administer the program. John questions, "How do we keep the bickering out of the program?"

He suggests that maybe the climbers should maintain a log, like a pilot, scuba diver or trucker. The log would document every climb and project and provide support for professionalism.

Tower companies, carriers and others must embrace it

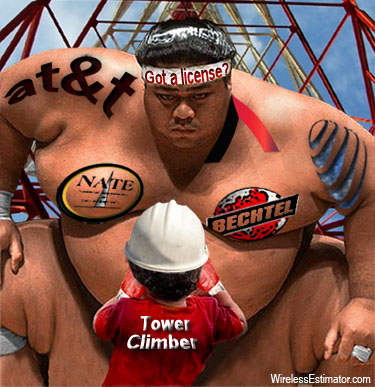

If authority=power then one question may have a clear answer. The money has always had the power in the tower industry. The power is wielded by AT&T, Verizon, Sprint, broadcasters, the railroads, utility companies, oil companies, tower owners and government.

Through the clients, the power is passed to the large general contractors such as Bechtel, Black and Veach, General Dynamics and Edwards and Kelsey. There is little doubt that if the power demanded the license, a license would become a reality.

I have listened to the concern for years about climbers and tower technicians losing professional respect, a loss of income and the lessening of the profession by untrained bandits in the industry. It seems that a licensing process is a major step toward increasing the quality of both the workmanship and the safety in the tower industry.

Imagine the power to ensure compliance if you could not only fire employees for incompetence, but "pull their license" and fire the offender from the trade. Every person that I have discussed licensing with believes it is an excellent idea.

Although media focus is always upon fatalities in the industry, because it is a sensational news bite, worker injuries are equally as important in addressing a licensing program. Our industry has had its share of climbers who are now disabled for life because they weren't practicing safe climbing on the job site.

Why would insurance underwriters not welcome licensing as well? It could possibly result in lower insurance premiums for erection, service and maintenance companies.

If you agree, we can make it happen. If you don't agree, why not? Tower workers are the most "get it done" people on God's earth; there is no such thing as impossible.

Wisconsin's state government has a process to establish licensing and it is fairly streamlined. They have a package with full processes available on line. What about your state? What about the Federal process?

Is NATE the answer?

We can start with our own organization, The National Assocation of Tower Erectors. What can NATE do? Is NATE willing to do anything?

Maybe NATE is not the association to develop or administer licensing, but NATE should be the voice of the industry. NATE can support the concept; NATE can invite the powers to the table to discuss the need, the details of structure and administration.

NATE has demonstrated the ability to get our industry's attention with OSHA. Maybe they need to lobby with some other government agencies.

If not NATE then who should carry the torch? Maybe we need to band together and form a special organization just for the purpose of establishing a license process.

You can just ignore Destry's plea until it happens to you or your associates or you can pick up the phone, write a few letters and actively work to make licensing a reality. How many more climbers will die before we find solutions?

* * * * * * *

Winton W. Wilcox Jr. is Founder and President of ComTrain LLC, Monroe, WI. Winton is an accredited Jr. College instructor in both California and Wisconsin and has authored a publication on tower climbing safety and rescue. He is also a frequent contributor to WirelessEstimator.com and other national media. Mr. Wilcox's comments are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of WirelessEstimator.com. Winton W. Wilcox Jr. is Founder and President of ComTrain LLC, Monroe, WI. Winton is an accredited Jr. College instructor in both California and Wisconsin and has authored a publication on tower climbing safety and rescue. He is also a frequent contributor to WirelessEstimator.com and other national media. Mr. Wilcox's comments are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of WirelessEstimator.com.

| Add your input or view the comments regarding the pros and cons of licensing tower technicians who work on elevated sructures. Visit the WirelessEstimator forum. |

|