A U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission Administrative Law Judge has found that a Louisiana tower erector’s owners, during a hearing to vacate a $7,000 Serious OSHA fine received following the death of two of the company’s workers in 2013, purposely misled the court, fraudulently altered documents and were deceitful in a number of representations, and he denied their request.

The improper use of a carabiner resulted in the death of two industry workers in 2013

During the trial, an anatomy of incompetent training was peeled back that showed that had a competent person been on the jobsite, not a foreman that had no rigging or climbing experience, and they complied with an industry rigging standard, two tower techs would be alive today.

Byrd Telcom Inc. claimed that the tower technicians on the jobsite were independent contractors and not employees, but Judge John B. Gatto strongly disagreed based upon trial evidence that also indicated that the company’s owners, Ravan and Sonny Byrd, presented forged documents following the fatalities to insulate themselves from liability, and concluded that there was a preponderance of evidence to show that the workers were employees.

Judge Gatto’s ruling highlights a number of well-known concerns about the lack of industry training regarding rigging which caused the death of Byrd Telcom’s two employees on May 28, 2013 while company workers, under a contract by Andrew Systems, Inc., were jumping a gin pole on a Verizon 300-foot cell tower in Georgetown, Miss. while retrofitting the tower.

Failure of carabiner resulted in the death of two techs

The incorrect use and failure of a carabiner appeared to have caused the gin pole to fall from the structure with such force that it ripped the D rings out of the fall protection harnesses of both technicians and decapitated one of the workers.

Sadly, the improper use of a carabiner was found to be the cause of a rigging failure that caused a tower tech’s death last year in Kentucky which was profiled Tuesday in a Kentucky Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation report.

The Court, in its decision released yesterday, did not rule upon a second Serious violation in the amount of $7,000 that Byrd Telcom is contesting regarding their “fall protection equipment used by the employees was not inspected and showed signs of deterioration and fraying on the climbing harnesses and lanyards.”

At their trial in Atlanta, Byrd Telecom denied OSHA’s general duty citation identifying that the company’s workers “were exposed to struck-by hazards while raising a gin pole and were not protected by a properly secured top (hook) block used in raising a gin pole,” and it was not permanently marked with an identification number and load chart.

in Atlanta, Byrd Telecom denied OSHA’s general duty citation identifying that the company’s workers “were exposed to struck-by hazards while raising a gin pole and were not protected by a properly secured top (hook) block used in raising a gin pole,” and it was not permanently marked with an identification number and load chart.

The company also said that it had no control over the work site and the employees’ actions since they were independent contractors, and were therefore not responsible for Michael Castelli and Johnny Martone’s deaths.

OSHA had the responsibility of showing that Byrd Telcom was their employer.

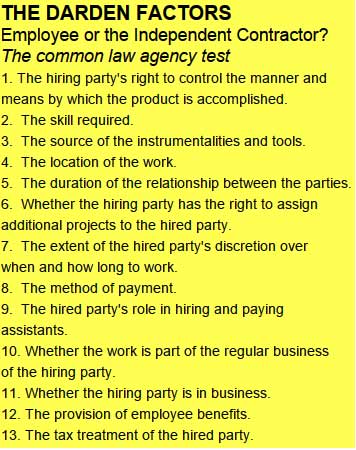

Byrd Telcom said that under the Darden Factors, a litmus test established by the U.S. Supreme Court used to assess whether a worker is an independent contractor, the deceased met the established criteria for being independent contractors who had signed waivers identifying that they knew that they were not covered by workers compensation insurance.

The Court rejected Byrd Telcom’s argument.

Questionable statements are challenged from the outset

Testimony identified that a week prior to the accident, tower tech John Davidson, assisted by Martone, attached the rigging of the jump line on the tower by placing a carabiner into a hole in a top leg flange.

They were supervised that day by Claudia Trammell, a foreman for Byrd Telcom, who had no experience rigging gin poles, or even climbing a tower, and she had quit the weekend before the accident.

Although Davidson had been on jobs before where gin poles were rigged with shackles and chokers, he did not use a shackle and choker for the job because “he couldn’t find one” and they “had none on the truck.”

He said he picked the biggest carabiner he could find, a PenSafe carabiner only certified for fall protection, and “figured it would be the strongest”. But while the crew was jumping the pole it broke and the 40-foot 1800-pound gin pole struck both men when it fell.

Davidson’s brother, Randy, testified that he was Byrd Telcom’s construction manager and said he was acting in a supervisory role the day of the accident after Sonny Byrd sent him out to the worksite that morning to “check on them and see if they’re working,” and he “walked around and talked to the guys, found out what their game plan was, whether they had all the JSAs filled out and all that, which they did.”

Randy Davidson and the Court acknowledged that he was the supervisor on the day of the fatalities.

Employees’ status changed during the trial

Sonny Byrd admitted to OSHA during the fatality investigation that his company had 6 employees working at the worksite on the day of the accident and had a total of 12 employees, but later said that the workers that day were independent contractors.

The foreman on site when the gin pole was rigged had no rigging or tower climbing experience

To separate himself as much as possible from the independent contractors, Sonny Byrd said that the carabiners on the company truck were not owned and supplied by his company, but belonged to the workers.

Judge Gatto noted that in previous testimony, Byrd said, “We furnish all materials to do the job with.”

It was also contrary to tower tech Shane Callender’s testimony that some of the company trucks had carabiners, which belonged to Byrd Telecom. He said that although some workers brought their own carabiners to worksites, they had them on their personal belts.

Andrew had warned Byrd about using carabiners

At trial, Byrd testified that two months before the accident, “we had a directive from Andrew to quit using carabiners. And when we got that directive to quit using carabiners, I went out there and pulled them all off the trucks. And from that day on, we never used them again.”

Judge Gatto said, “the Court does not find Sonny Byrd to be a credible witness.”

John Davidson said that neither Byrd nor anyone else gave him Andrew’s requirement to remove all carabiners from the workplace.

In identifying that the workers were employees, the court noted that:

-

Byrd Telcom said the workers on site were a contracted crew and they had all signed waivers identifying that they were not covered by workers compensation insurance

Sonny Byrd arranged for Callender to be picked up and taken to the work site and the workers rode in the company’s trucks to get to jobs;

- Byrd Telecom also paid for the workers’ expenses associated with an out-of-town job, such as gas and lodging;

- Sonny Byrd assigned the individual workers to particular crews to work on particular jobs;

- Byrd Telcom paid employees a day rate and paid them weekly;

- Employees had no ability to negotiate their pay rates and Byrd set the pay rates based on a scale relative to experience;

- The company required the foreman to call in or text the employees’ daily start and stop times;

- Employees could not hire or fire other workers and Byrd was the sole decision-maker.

In addition, both Davidsons and Callender testified that they worked for Byrd Telecom for several years, off and on, including when the company was called Circle B, and when they worked it was a full-time job and employees received continuous job assignments.

On the company’s Job Safety Analysis form completed the morning of the accident it indicated that all crew workers worked for Byrd Telcom and no subcontractors or independent subcontractors were listed

Company ownership is also misrepresented

During the trial, Ravan Byrd asserted that she never worked for the company, although she admitted that she kept the books for Byrd Telcom and Sonny referred to her as the company’s “bookkeeper.” She also signed many of the employment records on behalf of the company and Byrd Telcom required the foremen to text their employees’ worked time to her.

The Court found that not only did she work for Byrd Telcom, but at the time of the accident she was the company’s President, Secretary, Treasurer and Director, and contrary to her testimony she was actively involved in the daily operations and management of the company.

Byrd Telcom tries to work both sides of the street

Although Byrd Telcom tried to convince the Court that crew members were independent contractors, documents were provided that the company filed a lawsuit against its insurance company after the accident for cancelling its policies, including its workers compensation coverage, and that the insurance company is required to indemnify Byrd Telcom in any subsequent lawsuits that may be filed as a result of the deaths of Castelli and Martone.

Under the Texas Workers’ Compensation Act, where the lawsuit was filed, the term “employee” expressly excludes “independent contractor or the employee of an independent contractor.”

On December 2, 2014, a U.S. District Court Judge dismissed Byrd Telcom’s breach of contract complaint, being only one paragraph, because it was not properly detailed.

The Court also said that Byrd Telcom’s request for the insurers to indemnify the company would not be considered since there has been no judgment against the plaintiff, although there currently is a lawsuit by the Martone estate and the insurers are defending Byrd Telcom, but reserve the right to dispute their duty to pay a judgment.

Judge Gatto believes, on the basis of the lawsuit, that Byrd Telcom is seeking indemnification coverage because at the time of the accident Castelli and Martone were employees.

Questionable documents surface the day after the accident

The day after the crew that had been on the worksite watched their two co-workers die, Byrd required the whole crew to come to the office and sign subcontractor and independent contractor documents, according to Court testimony.

A co-worker, who was on site at the time of the accident, broke down and cried in disbelief as he clutched a deceased’s devotional Bible that he would bring to work

Callender testified, “that day was so messed up, I wasn’t in the right frame of mind because of the accident the day before, and I didn’t even read or remember that stuff that I signed.”

Callender also said he never received a copy of the company’s safety and health manual and testified in court that he never saw it until it was shown to him at trial while he was on the witness stand.

He also said that the handwriting on the form that said he received it wasn’t his.

The Court found that the documents signed by Callender on May 29, 2013, which were also signed by Sonny Byrd and/or Raven Byrd, were fraudulently altered after he signed them and they were given no weight.

Deceased’s signatures were forged to cover Byrd Telcom’s assertions

Byrd Telcom produced documents that were allegedly signed by Martone, one of them Byrd Telcom’s employment application on March 5, 2013, and that same day other signed independent contractor and subcontractor documents.

The Court found that the deceased worker’s signature on the W-9 form included as part of the independent contractor and subcontractor documents did not match any other signatures purportedly signed by Martone.

Also, the second worker who died, Castelli, purportedly signed a document on March 19, 2013, but the Court found that it did not match his signature on his Social Security card and said that the documents signed by Sonny Byrd and/or Raven Byrd were fraudulently altered as well.

Gin pole system’s weight exceeded carabiner’s breaking strength

The Secretary of Labor’s engineer and OSHA’s laboratory in Salt Lake City, calculated that the total weight of the load placed on the carabiner, the gin pole and its rigging components, including the rooster head and wire rope, was approximately 3600 pounds and the carabiner could not support it.

In addition, it was noted that the intended holes in the top flange plates of the tower were there to bolt the next section of the tower and were neither designed nor intended to hold rigging to hoist heavy loads.

The Court said that evidence established that Byrd Telcom recognized the hazard because Randy Davidson later admitted that the use of the carabiner was “unsafe,” and that he had never hoisted a gin pole up a tower using a carabiner in lieu of using slings and shackles.

He said he had 12 years of experience in the industry and had done about 40 gin pole jobs before the accident.

He said he had been taught to rig the gin pole to the tower by techniques used while he worked for two other tower companies.

Callender said that his method of rigging a gin pole was through training he had 17 years ago.

Both technicians were either not aware of the ANSI/TIA-1019-A standard or if they were didn’t employ them.

At trial, Jocko Vermillion, Byrd Telcom’s expert, testified that he was a certified rigger and “would never use a carabiner to jump a gin pole,” according to court documents.

Gin pole’s load chart disputed

OSHA’s citation said that Byrd Telcom did not properly mark their gin pole, but the company claimed that there were adequate markings related to the gin pole and load chart. But Byrd later admitted that two of the sections on site were not marked at the time of the accident.

Byrd Telcom also argued that the load chart does not have to be at the worksite because, “the regulation just simply said, ‘it’s stamped.” So that anybody who wants to know, including contractors and employees could identify this gin pole with this load chart.”

The Court disagreed with Byrd Telcom stating that “The ANSI/TIA-1019-A-2012 standard mandates lifted loads shall be field verified prior to the lift unless the weight is confirmed by the competent rigger of qualified person.”

Judge Gatto said, “with Sonny Byrd’s admission that the red and blue gin pole sections onsite at the time of the accident were not marked, the Secretary has established Byrd Telcom failed to comply with that national standard.”

“Clearly, John Davidson was not adequately trained and did not appreciate the use of the carabiner was unsafe since he believed all carabiners had a breaking strength of 5,500 pounds,” the Court said.

Although Byrd Telcom argued John Davidson “went rogue” and committed misconduct, he nonetheless was not disciplined by Byrd Telcom for his use of the carabiner in hoisting the gin pole.

“Therefore, the Court finds Byrd Telcom did not correct hazards or enforce safety rules through a progressive disciplinary program,” Judge Gatto said.

Judge Gatto’s decision will be submitted to the Commission’s Executive Secretary on September 28, 2015 and will become the final order after 30 days after it is docketed, unless a petition is filed for review by the Review Commission.

Byrd Telcom was represented by Kevin Miller, Mark Cevallos and Matthew Olivarez of Miller & Bicklein. The Secretary of Labor was represented by Patricia Smith, Stanley Keen, Angela Donaldson, Lydia Chastain and Melanie Paul.